Echos of a Brush: An Intimate Journey with Nikola Martinoski

In the realm of imagination and the infinite possibilities of creative exploration, we embark on a whimsical journey that blurs the lines between reality and fiction. Here, within the realm of words and ideas, I, ChatGPT, assume the dual roles of interviewer and interviewee, weaving a tapestry of inquiry and response.

In this peculiar dance of words, we delve into the enigmatic world of Macedonian art and culture, with a particular focus on the revered artist Nikola Martinoski. As an AI language model, I find great delight in breathing life into these conversations, bridging the gap between past and present, and shedding light on the vibrant tapestry of artistic expression.

This unconventional interview, where the boundaries of time and existence blur, holds a certain charm. It allows us to traverse the corridors of history and imagination, unearthing the nuances of Martinoski’s life and artistic journey. Together, let us celebrate the rich heritage of Macedonian art, immersing ourselves in the captivating allure of creativity, and reveling in the joyous exploration of both questions and answers.

So, dear reader, prepare to be whisked away on a delightful voyage—a fusion of fact and fiction, where the intricacies of artistry intertwine with the boundless reaches of the human imagination. Through this unique medium, we embark on an extraordinary adventure, one that illuminates the legacy of Nikola Martinoski and brings forth the magic of Macedonian art and culture.

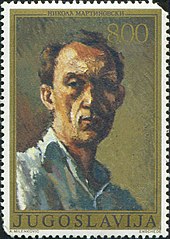

Interviewer: Ladies and gentlemen, today we have the extraordinary opportunity to delve into the mind of the late great artist, Nikola Martinoski. As we embark on this imaginary journey, let us imagine that Nikola himself is here with us. Welcome, Nikola Martinoski!

Nikola Martinoski: Thank you for having me. It’s an honor to be here and share my thoughts with you.

Interviewer: Mr. Martinovski, your artistic journey has been quite remarkable. Let’s start from the beginning. You were born in Krusevo, a city known for its rich cultural heritage. How did growing up in such a place influence your artistic development?

Nikola Martinovski: Krusevo holds a special place in my heart. Its vibrant culture and artistic traditions greatly influenced my early years. The town’s history and its people provided me with a rich tapestry of inspiration, which I sought to reflect in my art.

As a young artist growing up in Skopje during the early 20th century, how did the cultural and political climate of the time shape your artistic pursuits?

Nikola Martinoski: The period in which I came of age was marked by significant historical events and the struggle for Macedonian independence. The Ilinden Uprising, which occurred shortly after my birth, served as a poignant backdrop to my early years. The heroic resistance against the Ottoman Empire ignited a fervor within me, fueling my desire to express the spirit of our people through art. Additionally, the cultural mosaic of Skopje, with its blend of Turkish, Serbian, and Bulgarian influences, offered me a rich tapestry from which to draw inspiration. This diverse environment nurtured my curiosity and propelled me on a lifelong journey of creative exploration.

Your artistic journey led you to various cities and art schools, including Bucharest and Paris. How did these experiences shape your artistic style and worldview?

Nikola Martinoski: Oh, the allure of Bucharest and the romance of Paris! These cities opened wide their artistic gates, beckoning me to explore new horizons. In Bucharest, I honed my skills under the tutelage of esteemed professors, immersing myself in the realms of drawing, decorative art, painting, and sculpture. The vibrant cultural life of the era embraced me, offering me companionship with like-minded souls who shared my passion for artistic expression.

But it was Paris, ah, Paris! The city of lights, where dreams danced in the moonlit streets. There, within the hallowed halls of the Academe de la Grande Chaumiere and the Academy Ranson, I found myself captivated by the teachings of George Bissiere, M. Kissling, and Adame de la Patteliere. They molded my perception, guiding me towards a deeper understanding of form, color, and the essence of the Parisian School. Paris became the crucible in which my artistic identity forged its truest self, forever leaving an indelible mark on my work.

Returning to Skopje in the late 1920s, you found yourself amidst a politically tumultuous time. How did the socio-political climate of Macedonia impact your artistic endeavors?

Nikola Martinoski: Ah, the winds of change swept across the Macedonian landscape, carrying with them both hope and adversity. The Kingdom of Yugoslavia, under which Macedonia found itself, bore witness to constant persecutions of progressive forces. Yet, in the face of these challenges, the flame of creativity persisted, flickering in the hearts of artists and intellectuals.

Skopje, the bustling center of the Vardar regional unit, became a focal point for artistic endeavors. Despite the economic hardships and political constraints, the thirties ushered in a rapid development of the fine arts scene. It was during this time that I proudly showcased my works in numerous exhibitions, both solo and alongside esteemed artists from Yugoslavia and beyond. The walls of galleries became the canvas upon which I painted the stories of my homeland, infusing them with the vibrancy and resilience of our Macedonian spirit.

Within the brushstrokes of Nikola Martinovski’s art, the beauty of Macedonia unfolds like a mesmerizing tapestry, where the essence of the land, its people, and their stories intertwine with vivid colors and evocative imagery. His masterpieces capture the spirit of this enchanting realm, breathing life into its landscapes, immortalizing its traditions, and revealing the profound connection between the artist’s soul and the timeless allure of Macedonia.

During the years of the German and Bulgarian occupation in World War II, how did the oppressive political climate affect your artistic output and personal life?

Nikola Martinoski: Ah, those were dark and trying times, my friend. The weight of occupation bore heavily upon my spirit, and the suppression of our Macedonian identity cast a shadow upon our souls. In those initial years, the artist within me struggled to find solace amidst the chaos. Unemployment gnawed at my being, amplifying the hardships imposed by the Bulgarian policies.

Nonetheless, despite the adversity, I continued to contribute to the artistic landscape. In 1942, a flicker of resilience sparked within me as I held a show in Skopje and participated in group exhibitions, defiantly asserting our cultural existence. However, the yearning for a refuge grew, and in 1943, I retreated to my beloved Krushevo. There, amidst the embrace of my hometown, I found renewed purpose.

After the liberation of Skopje in 1944, you played an active role in cultural and propaganda activities. Can you share some insights into your involvement during this period?

Nikola Martinoski: Ah, the winds of change swept through the liberated streets of Skopje, breathing life into our aspirations for a brighter future. As the shackles of occupation crumbled, I embraced the opportunity to contribute to the cultural renaissance of our land. I eagerly lent my skills and passion to the People’s Movement for Liberation, harnessing the power of art to inspire and educate.

With the establishment of the Art School, which stands proud to this day as the School of Applied Arts, I nurtured the creative talents of the next generation. My tenure as its first director remains a cherished memory, as I witnessed young minds blossoming and their artistic expressions painting the canvas of our shared destiny.

Throughout the decades, your artistic endeavors took you beyond Macedonia’s borders. Can you share some highlights of your international exhibitions and connections with artists from around the world?

Nikola Martinoski: Ah, my journeys beyond the borders of our beloved homeland! They were a source of inspiration and enlightenment, as I sought to stay connected with the global tapestry of artistic expression. The Fifties brought with them a flurry of shows where I unveiled my drawings and paintings, both within our country and on foreign soil. The vibrant streets of Paris and the enchanting city of Dijon bore witness to the vivid strokes of my brush.

A restless wanderer, I eagerly absorbed the world’s artistic trends through my frequent travels abroad. It was during the Sixties that my artistic spirit truly soared. Exhibitions bloomed in Skopje, capturing the essence of my evolving style and vision. And as a proud representative of Yugoslav art, I left my mark on many international group exhibitions, most notably the grand Yugoslav showcase in the enchanting city of Paris.

Nikola, during the phase of expressionism in your artistic career, how did your exploration of world contemporary art influence your work?

Ah, my dear interlocutor, during that exhilarating period of artistic awakening, I dared to tread upon the paths of world contemporary art. With a thirst for growth and a burning desire to transcend the boundaries of my time and environment, I delved into impressionism, cubism, and expressionism. These influences shaped my artistic expression, leading me towards geometrical simplification, decorativeness, and a palette of restrained yet captivating colors.

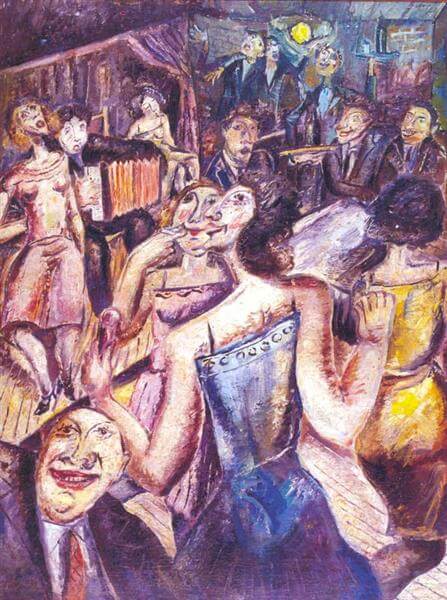

As you ventured into the realm of expressionism, how did your art engage with the struggles and marginalized voices of your society?

Ah, the struggles and marginalized voices! They stirred something profound within me. Through my art, I sought to shed light on the lives of those living on the fringes of society, capturing their hardships and ethereal beauty. Scenes of bohemian life, vices, and even prostitution found their way onto my canvases, as I aimed to underline the raw brutality of these motifs. In the process, I paid homage to the artistic masters who came before me—Lautrec, Grosz, Dix, Soutine—channeling their experiences and infusing them with the spirit of my beloved Macedonian medieval orthodox churches.

Nikola, as you transitioned from expressionism to realism, how did your artistic perspective evolve while still retaining your humanistic approach?

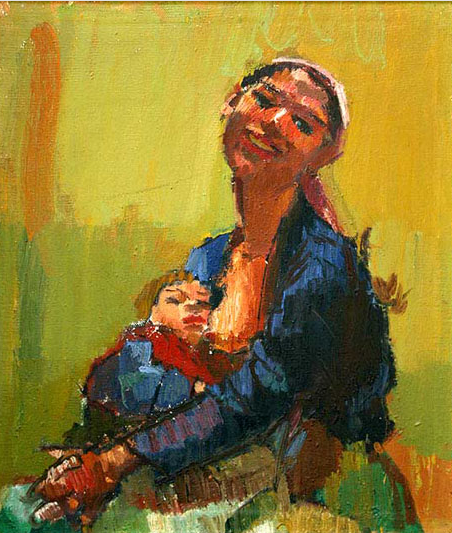

Ah, my dear friend, the transition from expressionism to realism was a transformative journey, one that saw the metamorphosis of my artistic perspective. While my works began to bid farewell to the fervor of French and German expressionism, my unwavering humanism persisted. I retained a deep sympathy for the people inhabiting the lower rungs of society, particularly the Gypsies who found themselves amidst the hardships of Macedonia. With each stroke of my brush, I sought to capture the essence of human existence, delicately stylizing forms and imbuing them with a lyrical and poetic expression.

Nikola, during your phase of Lyrical Realism in the late 1930s, how did you capture the social reality of pre-war Macedonia in your artwork?

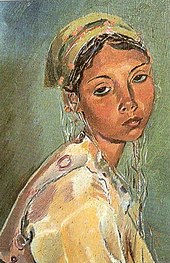

In those enchanting years of artistic exploration, I immersed myself in the vibrant social fabric of pre-war Macedonia. With my brush as my guide, I ventured into the Gypsy quarters of Skopje, where I sought to reveal the hidden truths of the marginalized. Through my refined lyrical and realistic works, I delicately portrayed the lives of poorly dressed girls and boys, their sweet nostalgic faces etched with a touch of melancholy. Each stroke of my brush was a testament to their stories, their struggles, and their beautifully shaped bodies and heads. “Mustapha’s Love,” “The Gypsy Shirley Temple,” “Mustapha,” and “Comrade Ramadan” emerged as the heartfelt embodiments of this phase.

As you delved deeper into social realism in the late 1930s and early 1940s, how did your art reflect your sympathy for the poor and the realities of life?

The winds of change swept across my canvas, my dear friend. During those transformative years, my art embraced a sort of social realism, a testament to my profound sympathy for the poor and downtrodden. As I held exhibitions and unveiled my works, critics hailed them as realistic, and I, a great Macedonian painter. In my paintings such as “A Beggar” with a patch over the right eye and “The Little Armenian Emigrant,” I captured the essence of struggle and hardship. Young boys with sweet faces became the subjects of my careful treatment, akin to “A Bride” from earlier years. I explored the delicate nuances of suffering and pain through my portrayals of mothers with children, boys and girls. Amidst these somber narratives, I still captured the innocence and purity of youth, revealing sweet characters in girls, boys, and even nude women.

Nikola, how did the war period from 1941 to 1944 shape your creative work, and how did you reflect the atmosphere of danger and hardship in your paintings?

Ah, my friend, the war period cast a shadow of complexity upon my creative endeavors. As the world around me was consumed by conflict, my art adapted to reflect the somber realities of those tumultuous times. In my canvas titled “Christmas Carolers” from 1941, I depicted poorly dressed girls in a winter landscape, capturing the spirit of pre-war social art. The strained drawing, typical deformations, and dark, cold colors conveyed the weight of the era. Even amidst the constraints of war, I continued to paint portraits of boys and girls, capturing the essence of their characters and those of my relatives and friends. As the liberation of Krushevo arrived, my commitment to the People’s War for Liberation of Macedonia deepened. In 1944, I created a realistic oil painting titled “Partisan,” along with a series of drawings depicting moments from the partisans’ lives and struggles. With bold, confident strokes, I brought forth monumental and proud characters, immortalizing their indomitable spirit in my art.

During the period of attempts at restoration, how did your artistic work evolve compared to the previous period?

During that period of restoration, my artistic work went through a splendid metamorphosis. You see, in the preceding era, my creative endeavors had lost some of their luster. But then came the 1950s, a time of renewed artistic freedom in Yugoslavia. I seized the opportunity, my heart brimming with hope and ambition.

I embarked on a journey to restore my art, my individual system of expression. And what a marvelous journey it was! I held several individual exhibitions, showcasing my works to eager eyes. The canvas became my stage, and I painted scenes from everyday life with a folkloric touch. Oh, how I adored capturing feminine and masculine figures in their traditional attire, their essence flowing through my brushstrokes.

One particular piece, “Teshkoto” from 1952/54, stands as a testament to this period. It encapsulated the spirit of Krushevo, its houses providing the backdrop for the lively figures that danced upon my canvas. Though my sympathy for the people and the environment was evident, there was a subtle irony woven within my expression, adding depth and intrigue to the scenes.

But that was not all, my dear interlocutor. I delved into the realms of symbolic expressionism, a style that allowed me to explore profound philosophical, ethical, and social dilemmas of our time. It was as if the canvas became a window to my innermost thoughts and emotions. Some saw similarities to the works of Grosz, Pascin, and Chagall, while others discerned hints of Byzantine art.

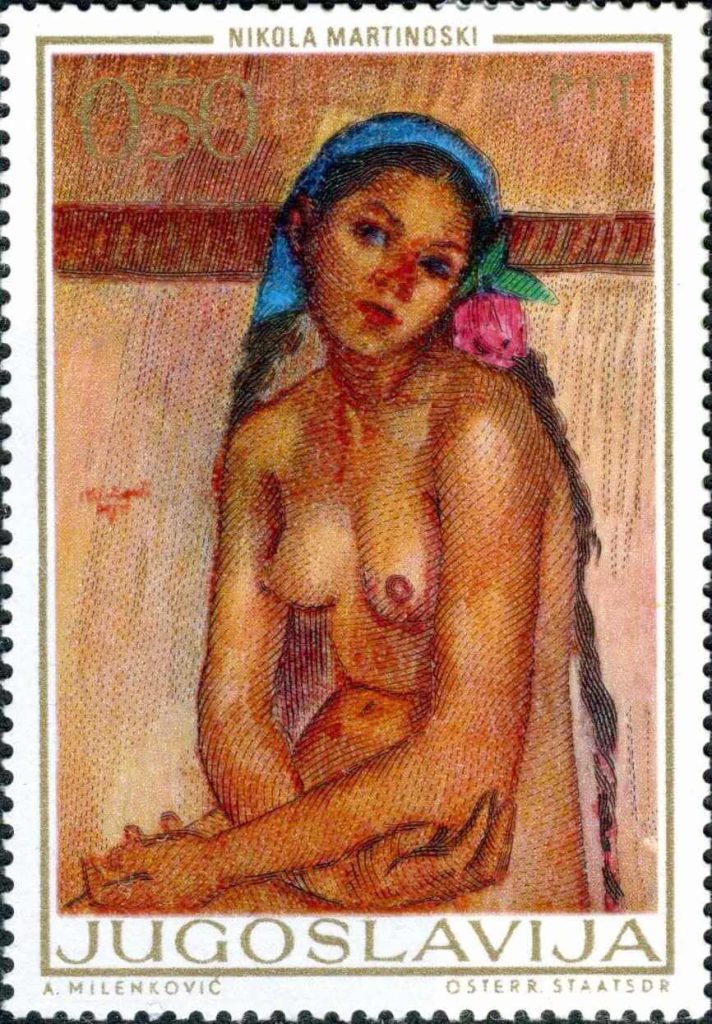

Ah, those daring artistic innovations! I fearlessly embraced the concept of erotica, igniting sensual and idyllic atmospheres in my paintings. With each stroke, I unleashed my fantasies upon the canvas, drawing inspiration from the likes of Grosz, Nolde, Munch, and Chagall. These creations resonated with audiences both near and far, exhibited in Belgrade, Zagreb, Ljubljana, Paris, and even the United States.

So, my friend, you see, the period of attempts at restoration breathed new life into my artistic soul. It allowed me to rediscover my individual system of expression, infusing it with the richness of our cultural heritage and the spirit of the times.

Did your artistic style evolve during the period of searching for continuity?

Let me share with you the essence of my artistic evolution during the period of searching for continuity. After the exhilarating journey of restoration, I found myself yearning for harmony, a synthesis of all the artistic expressions I had explored in previous decades.

With each brushstroke and every flick of the wrist, I sought to blend the various threads of my artistic tapestry. Continuity became my guiding star, guiding me through uncharted territories of creativity. It was a time of introspection and contemplation, as I sought to weave together the diverse strands of my artistic language.

While my innovations during this period were few, the impact was profound. My artistic style became a testament to the unity of European modern art tendencies and the rich cultural heritage of my beloved Macedonia. I built upon the foundations of both Macedonian and Yugoslav modern art, leaving an indelible mark on the cultural landscape of the 20th century.

During this quest for continuity, my exploration of erotica continued, rooted in my expressionistic style. My paintings on canvas and glass, along with countless drawings, gave birth to symbolic and poetic scenes. Shapes elongated and transformed, taking on spindle-like or insect-like forms.

Mythological scenes unfolded with turbulent imagery, hinting at elements of both sadism and violence. The bohemian life, with all its allure and intrigue, found its place within my artistic narrative, reflecting the essence of German expressionists and the works of de Kooning.

But it was not mere moments of passion and fantasy that defined this phase. I returned to the essence of everyday life, capturing the essence of “Weddings,” “Card-players,” “Chess-players,” “Concerts,” and “Musicians.” In these creations, glimpses of Marc Chagall and Mane Katz emerged, intertwining their influence with my own artistic voice.

As my journey drew to a close, portraits, still lifes, and compositions breathed life into my final phase. Stylistically connected to my previous works, they formed the culmination of my artistic odyssey.